A Lipton bag in boiling water was all I knew about tea before our trip to London in 2011. There, we went to afternoon tea twice, a mid-afternoon sit down where you drink tea and eat finger sandwiches and desserts, and I was baffled when the server gave me a many-page menu full of teas I could choose from. Who knew there was more to tea than just a simple black and green? I certainly didn’t.

My first cup of Lapsang Souchong in London.

After trying Lapsang Souchong, a black smokey tea, suggested by our server, I realized how much I had to learn. When we got back to Chicago, I visited the Coffee and Tea Exchange in our neighborhood and bought a few new kinds of tea to try. I felt fancy because I had to buy a tea ball and my own disposable tea bags because the tea I purchased was loose leaf.

Yet after visiting six of the top 10 tea producing nations during the last two years, I realized even after branching out to loose-leaf tea, my knowledge of the tea world remained quite small. So, let me tell you all about the world’s most popular beverage aside from water.

Who invented tea?

You can’t learn about tea without knowing its origin. Legend has it in 2737 BC, Emperor Shen-Nung (also spelled Shen Nung, Shen Nong, and Shennong) was busy boiling his drinking water when a few leaves from a nearby bush landed in it. They provided the water with a unusual color and a delicious taste, and tea was born.

Where does tea come from?

The bush which shed its leaves into the Chinese Emperor’s drink is known as Camellia sinensis. This same plant, a species of evergreen, is responsible for a majority of the tea in the world. From that plant alone, you can get six categories or types of tea: black, green, oolong, yellow, white, and dark.

Women working in the tea fields of Sri Lanka.

The difference between the tea types lies in the specific leaves or flowers of the plant used to make the tea and the oxidizing and fermentation processes which I will explain below.

And, because there isn’t already enough information to keep straight, enter Rooibos, an herbal tea. Rooibos comes from a red bush in South Africa called Aspalathus linearis and is not related at all to the rest of the teas. Since I haven’t been to South Africa yet, I am far from an expert on Rooibos, so I will stick to teas from the Camellia sinensis plant. Other “tea” that isn’t technically tea include chamomile and mint.

Where is tea grown?

Tea is grown in more than 60 countries around the world, but the top 10 countries producing the most tea according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization are China, India, Kenya, Sri Lanka, Turkey, Indonesia, Vietnam, Japan, Iran, and Argentina.

There is a list of each country at this fantastic site.

Is there a difference between oxidizing and fermentation?

Sometimes you can use two words interchangeably and it’s fine. This isn’t one of those times.

When we were learning about the difference between black and green tea, we were told often that it was the fermentation process which separated them. However, what was lost in translation was that it is actually oxidation, not fermentation taking place in a majority of teas.

Oxidizing is essentially the browning of the leaves which happens with oxygen after the cell structures within the leaves are ruptured. Fermentation requires an added organism like bacteria, mold, or yeast in order to start the process of converting sugars into acid, gas, or alcohol. A majority of tea types do not require the addition of organisms and are simply being oxidized. The only exception to this rule is dark tea, also known as fermented tea, which includes Pu’er. These teas actually have bacteria or mold reacting with the leaves, causing fermentation.

How is tea made?

While each type of tea looks, smells and tastes different, they actually all go through similar processing.

Graphic from the Specialty Tea Alliance (wulong is a different spelling for oolong.)

Step 1: Picking/Harvesting

Depending on the quality or kind of tea and the size of the operation, harvesting can take place either by hand or machine. Tea is a quick-growing plant and depending on the location can be harvested several times a year. For example, parts of China harvest their plants four times a year.

A photo which shows how waxy and tough the tea leaves are before processing begins. Photo from here.

Step 2: Withering

Once the leaves have been harvested, they are brought to the factory to continue processing. First up, the leaves are laid out on mats and left in a temperature controlled area to soften and wither. The tea is rotated to make sure each leaf receives proper airflow, ultimately reducing the water content of the leaves. This is necessary because the leaves of the tea plant are quite thick and waxy, similar to a holly leaf or kaffir lime leaf. This process is skipped, however, during the making of dark teas like Pu’er.

Tea leaves withering on the floor of a tea factory. Image from here.

Step 3: Maceration/Bruising/Rolling/Cutting

Once the leaves have withered they are moved to a machine which helps to break down the cell walls in the leaves. This process can take many forms depending on the type of tea (black, green, oolong, etc.) and also the quality of the tea. For finer tea, the leaves are rolled or twisted while other tea is crushed and even cut during this process. The leaves for black or dark tea go through this step multiple times to reach the proper levels of bruising which allows for the next step: oxidation.

Step 4: Aging/“Fermentation”/Oxidizing

This is the most important step in separating out the different styles of tea. As mentioned above, fermentation and oxidation are terms which are used interchangeably for this step. However, this step doesn’t actually add any organisms required for true fermentation and instead is simply a reaction from the cell walls being broken during the bruising process. The reaction, caused by enzymes in the leaves, causes the leaves to turn brown. The leaves are watched particularly closely during this process because allowing the leaves to progress too far here would ruin the tea. This step is skipped when making green tea, an unoxidized tea.

Tea changes colors during oxidation and is monitored closely during this step. Photo from here.

Step 5: Fixing

Stopping the oxidation process and preserving whatever green is left in the leaf is done with heat and can be executed in a couple different ways. Regionally, there are variations in the fixing process including steaming, frying, or roasting, which offer different flavors to the tea.

One version of fixing is roasting the tea in a wok. Photo from here.

Step 6: Drying

The final step is drying, in order to remove any remaining moisture and to promote a shelf-stable leaf.

Now, the tea is ready to be packaged and sold. Depending on the tea category, most of the leaves can go from growing in the field to packaged in anywhere between a few hours or a few days. Obviously, the dark teas require a lot more time for fermentation, so those will take longer than the white, green, oolong, or even black teas which can be processed quickly.

Tea drying in the sun after going through processing. This final dry makes the tea shelf stable. Photo from here.

What are the Different Tea Types?

The Camellia sinensis plant is responsible for all six different types of tea, read on to learn more about each tea type.

White Tea

This is the least-oxidized of all the teas and is made of new, young tea leaves and buds. The harvest window is quite small for white tea, just a few weeks in the spring, and similar to Champagne in that proper white tea comes only from the northern district of Fujian, China. There are five styles of white tea: Silver Needle, White Peony, Tribute Eyebrow, Noble Long Life Eyebrow, and Fujian New Craft. White tea has a mild flavor and is quite delicate to brew. It requires a lower water temperature (175-185°F) and a quick steep (1-3 minutes) compared to other teas. It’s mild flavor also has encouraged lots of tea shops to blend fruit or flowers with it.

This white tea is from China, you can see the white flowers if you look closely.

Green Tea

The oldest of all the tea types, green tea is fully unoxidized, meaning it skips the aging step altogether and goes directly from bruising to fixing. Typically during the fixing process, green tea is either pan-fried or steamed, depending on the region, and retains its green color giving the tea its name. Unlike white tea, green tea can be harvested several times a year and is grown all over the world. Yet, it wasn’t until the late 19th century that green tea made its way to the Western world. There are dozens of variants of this type of tea, including Gunpowder, Longjing, Yun Wu, Gyokuro, Sencha, Matcha, Tencha, Genmaicha, Hojicha, etc. To brew, it requires a mild water temperature (180-185°F) and a quick steep time (3 minutes). Water which is too hot will release tannins and leave the tea bitter. Similar to white tea, green tea also provides a mild flavor that can be the base for additional flavors such as Jasmine to create other well-known teas.

This is green jasmine tea, the white pieces are the jasmine.

Oolong Tea

Also known as wu-lung, wulong, or wu long; oolong tea slides in between green and black tea when it comes to oxidation. This partially oxidized tea is actually my favorite and is typically harvested once a year. Handpicked, only the top three leaves of the Camellia sinensis plant are used for this tea which originated in China, but is now grown across Asia. Different from other teas, when you steep a quality oolong, you are actually brewing entire leaves, not just pieces of leaves. This is because oolong is rolled, not chopped, during processing. The rolling process has remained the same for thousands of years and is responsible for its name. Oolong roughly translates to “black dragon” which is meant to describe the shape of the dried oolong leaves before they are steeped. Since oolong tea can be oxidized for varying lengths and grown in a variety of climates and altitudes, there are hundreds of oolong teas out there. However, the rule of thumb for brewing oolong is to keep the water between 185-200°F, and steep for 3-5 minutes. Oolong is also special because the leaves can be steeped several times, each brewing creating a different, often deeper, flavor.

You can see the rolled dried oolong in the bowl, while the leaves next to it have already been steeped and unrolled. Quality oolong will always be made of whole leaves.

Black Tea

Easily the most popular tea in the U.S., black tea is fully oxidized, often going through the bruising and oxidation process (steps 3 and 4 listed above) several times. Repeating this process leaves the tea in three states: whole leaf, broken leaf, and tea dust (also known as fannings). These three states, along with the specific leaf processed, leads to the complex grading system only found in black tea. In Sri Lanka, it is common to buy tea with names such as FBOP (Flowery Broken Orange Pekoe) or FBOPF (Flowery Broken Orange Pekoe Fannings), so it is nice to understand the grading system. The leaves closer to the top are of higher quality, so Flowery Orange Pekoe is much better quality than a Souchong, while whole leaf is much better quality than broken leaf or dust/fannings. The flavor is also much stronger in the broken leaf or dust/fannings.

Graphic from here

The black tea you are using to make iced tea is probably broken leaf, which accounts for more than 90% of all tea sold in the U.S. Aside from black teas which are named by their grade, there are a lot of well-known black teas you might have had before; Assam, Darjeeling, Ceylon, and Kenyan just to name a few. Tea blends like English Breakfast Tea, Masala Chai, Russian Caravan, and Earl Grey are also made of black tea, and Lapsang Souchong, one of my favorites is a black tea which is dried over a pine fire giving it a smokey flavor. Black tea is best prepared at 206°F, with a steep time of 3-5 minutes. The only exception to this rule is a Darjeeling which is steeped best at 180°F for up to 3 minutes.

This was black tea we found in China, packaged in the traditional way which makes it look like a frisbee.

Dark Tea

Dark tea is the only tea which has gone through fermentation, not just oxidation. A majority of this tea comes from just three counties in the Hunan Province in China. While the specifics of the fermentation are closely guarded state secrets, we do know bacteria play a part, reacting with the leaves to change their chemistry and ultimately the flavor, aroma, and appearance of the leaf. These teas are like fine wine and improve with age, some lasting more than 50 years. This tea is a bit harder to find in the U.S. but is very common in China. Of the dark tea, the most well-known type is Pu’er. Dark tea is best made with water between 208-212°F and steeped for 4-6 minutes. Like oolong, dark tea can be re-steeped many times.

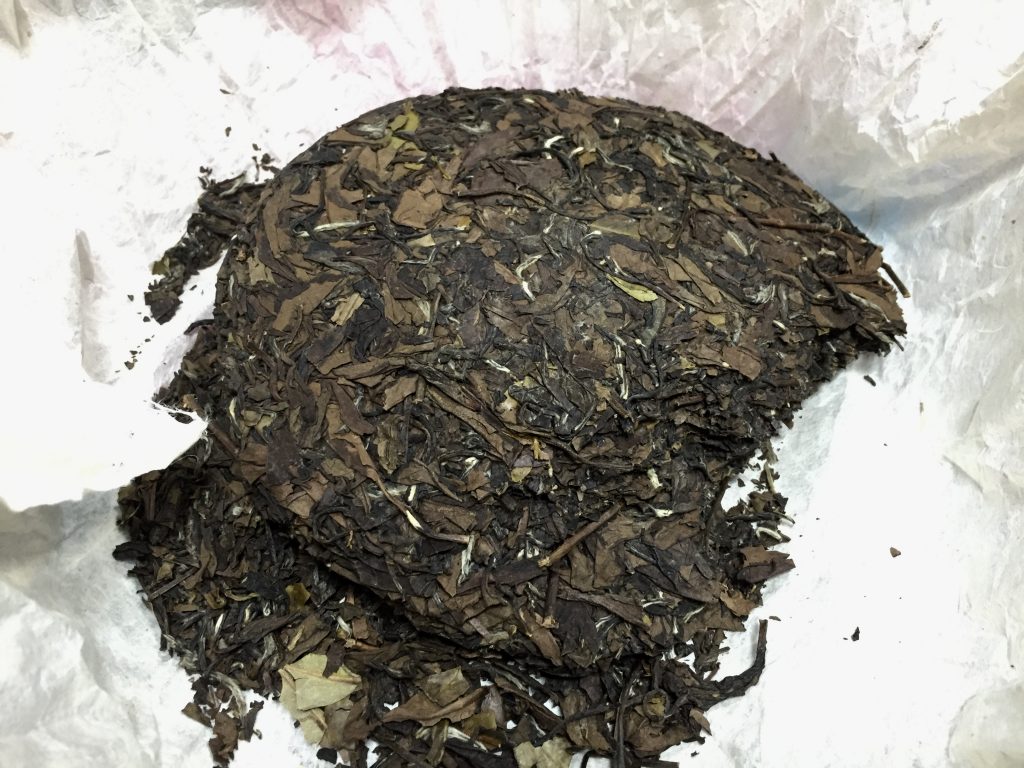

Here is a closeup of some Pu’er Tea. We tried this particular tea and weren’t fans. You can see how the fermentation process has really changed the leaves from a traditional black tea shown above.

Yellow Tea

Yellow tea is incredibly rare. Made only in China, this tea is time and labor intensive requiring the buds to be wrapped in a special cloth repeatedly for up to three days. This process is called smothering, which slows the oxidation process and concentrates the aromas back into the buds and creates a more mature flavor than a typical green tea. Because it takes 60,000 hand-picked buds to make 1 kilo of tea, the tea is primarily consumed by locals, and unfortunately, is a dying industry. If you are lucky enough to get your hands on some yellow tea, you should brew it between 170-180°F and leave it to steep for 1-3 minutes. It can also be steeped several times.

Yellow tea, photo from here.

Interesting tea facts

- What we refer to as a black tea, is actually called red tea in China. This is because of the reddish color the tea produces when it is brewed.

- Black tea was “discovered” in China during the mid-17th century. Up until this point, only green and oolong tea was consumed in the East. Legend has it that an army entered the Fujian Province and camped at a tea factory. While they were there, they disrupted the tea processing schedule, leaving the tea to oxidize for much longer than usual. This left the tea leaves, which were normally green, a dark color. In order to save the tea, a farmer placed the leaves over a fire to dry it out. What it produced was a smoky flavored tea, known today as Lapsang Souchong.

- Lapsang Souchong is one of my favorite teas, but those in the East, specifically China, call this type of tea “tea for Westerners.”

- Nearly 80% of the tea consumed in America is iced.

- Pu’er Tea was illegal to import into the U.S. until 1995.

- There are hand wrapped teas folded into beautiful shapes.

Do you still have questions about tea? Leave them in the comments.